Theatre Production 101

Our guide to getting started with theatre production for emerging producers and self-producing artists.

Introduction

The aim of this article is to introduce you to the process of producing a show. It serves as an overview of the process. It links you to other articles that talk in more depth about specific parts of the process. Visit the linked article to learn more about what a theatrical producer is.

If you are new to Producing Theatre.com, I recommend you start here and use this as a road map to the content. As you reach sections where you want to know more detail, click through to the recommended articles.

Remember, we update the site all the time, and we try and update the link to ensure you can find new material.

Now, let’s get into it …

Why self produce theatre?

Many people choose to become a producer, but everyone has their own personal reason for doing it. Yet, in most cases, there are some common themes.

Self-producing offers:

- More control over whether you work

- More control over what you create

- A chance to gain exposure

The benefits and advantages change depending on why you chose to choose to produce. As do the challenges you’ll face.

An artist might be tired of waiting for someone to hire them. Any artist can benefit from self-producing. Some good reasons to consider self-producing are outlined in the following articles:

A teacher might want to create a genuine theatrical experience for their students. This will likely require you to take on the producing role.

Planning your theatre production

The first step to any project is planning. You need a clear idea of the project and why you are doing it before you have any chance of success.

Goals

You need to set the primary goals of the production. These are your high-level goals. For example:

- To showcase my acting skills in front of casting directors

- To prove to local Artistic Directors that I can direct a play

You will typically know these goals instinctively. Think about what excites you about the project. What is it that you imagine as the outcome? This is where you find these goals. Write them down and own them.

Even though these goals are high level, you still need to make them SMART. That is Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. Every goal needs to be set according to this framework.

Goals set the direction of your production. They help you navigate problems as they arise. You should know how your choice moves you closer to achieving this goal for every decision you make.

Outlining the show

Your goals will help you outline what your theatre production looks like.

Think about this like the pencil sketch an artist does before they begin painting. This outline will end up covered in paint, and the audience will never see it, but it will always be there.

A framework that you can use to help you create this detailed sketch is one many people will be familiar with. The 5Ws (and 1H) refers to the classic interrogative questions:

- Why

- What

- Who

- When

- Where

Using these prompts, it is easy to create a plan that you can follow. From there, you can concentrate on filling your canvas, falling back on the guide when you need to.

Budgeting the show

All theatre productions rely heavily on a reasonable budget. It is part of securing your funding and managing the production. Every aspect of that production is represented in the budget, from wages to advertising. Your budget is both a planning and management document.

How you manage your finances dictates what you put on stage. You will need to balance what you can afford against what you want. It’s easy to create a great show with a lot of money—a limited budget forces you to think of creative solutions.

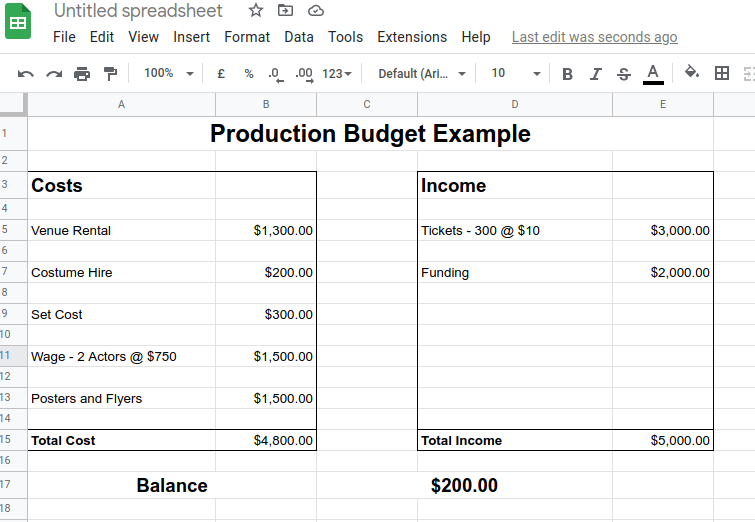

The basics

A show budget in its most basic form has three components:

- Income – the money you earn or raise

- Expenditure – the cost of staging the show

- The balance sheet – a comparison of the two

They relate to each other as follows:

- Income – Expenditure = The balance

If your income exceeds your expenditure, you made a profit. If your expenditure is the bigger number, you lost money. This is what you are trying to avoid.

For more detail start with our Budget 101 and Budget 201 articles.

You can do many things to make your budget more valuable as a planning document. Still, it always boils down to these basic ideas.

Planning your budget

For your budget to be helpful, you’ll need to make it before you have actual figures for:

- what you spend on staging the show

- how much money you made from selling tickets

- how much support you were given

This means you need to make estimates or projections for each of these things.

For costs, you can ring up and ask for quotes for as many things as you can think of. To work out your income from tickets, you will need to guess how many people are coming and how much you can charge. The support you’ll need is the difference between those numbers.

As you get new information, you’ll need to change the numbers and try and figure out how to bring the budget back into balance.

Managing your budget

Once you are confident you have figures in your budget that are realistic, you can use them as a spending guide. Try and make sure you don’t pay more than you planned for each item. If you have to spend more, work out where you can reduce your spending.

This applies to your income too. If you decide you need a certain number of tickets sold, you need to work hard to get many people to come. If you need a specific amount of funding to bridge the gap, then you’ll have to go find it.

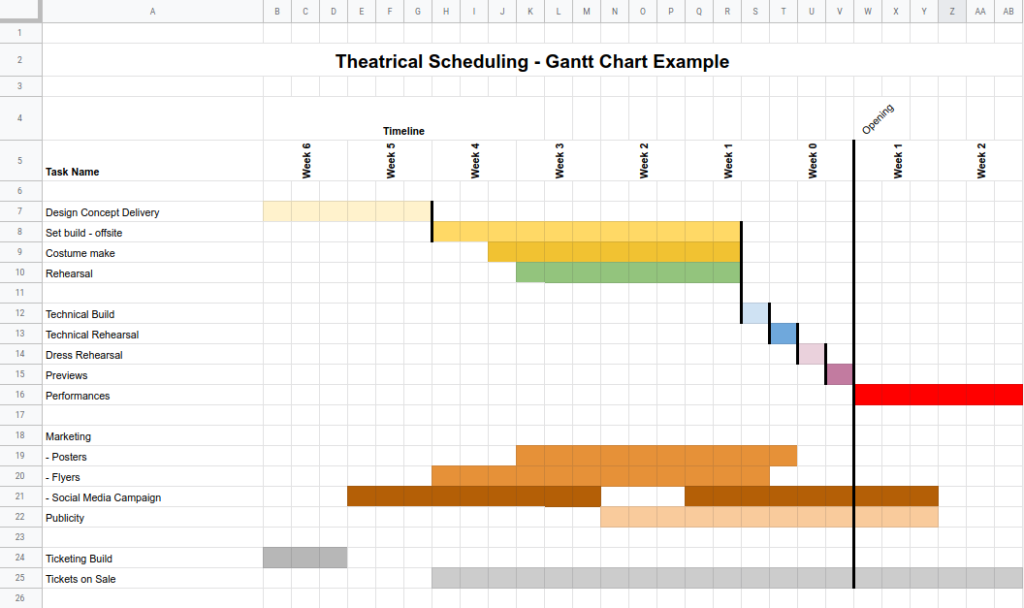

Scheduling for a theatre production

The schedule is the other central planning document that you’ll need to run a successful production.

Your schedule tells you when you need to finish a specific job or pay a particular bill. If you don’t meet these deadlines, you risk the quality of your show or even the performance itself.

Production schedule

This part of the schedule plans when you need to finish things like casting, rehearsal and design, so the show opens on time. It focuses on jobs and people.

For more on this check out this article on the principles of theatre production schedules.

Cash flow

Cash flow is where the budget and schedule meet. It focuses on making sure you have enough money when you need it. Your ticket income doesn’t arrive in time to pay many bills, so cash flow works out how you’ll manage that.

Building a team

Only work with people you trust and respect. If you don’t, you’ll spend a lot of time worrying. There is no point in micro-managing someone that you hired to reduce your stress!

Your director and designers need to be both artistic and reliable. Some of my worst experiences were with designers who had great ideas but didn’t know how to execute them and expected other people to give them the answers.

Your crew need to be people who can work without having their hands held. Their initiative is more important than experience if you don’t have much cash. You need an operator or SM who get work done. The same applies to other staff like publicists.

A rule of thumb is that you don’t want anyone around who isn’t taking work OFF your plate. The net result should be that you to do less than you would if you hadn’t employed them.

Choosing the right person

The right person isn’t always the best at what they do. You need to consider more than artistic talent when you choose to work with someone.

Make sure you dig into the work ethic, personality and experience of your team members. If you get someone who won’t work well with others or struggles to do their job, it can break your whole production. An actor who struggles to learn lines is a liability no matter how good their performance.

The right person is a whole package—a balance of skill and professionalism.

Casting a show

Your performers are part of the team like everyone else. It is important to remember to treat everyone with the same respect. Nothing will generate ill will in your production faster than the appearance that your performers are seen as more important.

Yet, you need to take special care with choosing your cast. It’s said that 80% of a good show is casting. This may be an over-simplification, but there are plenty of reasons it holds true.

- A director can only work within the performer’s capability.

- No amount of beautiful design can compensate for poor performances.

- Performers have a direct connection with the audience.

- An unreliable performer can derail the train during a performance.

A producer should make sure that plenty of time is allocated to selecting the right performers. This is time to be conservative.

Auditions

The best practice to ensure you cast the right people is to hold auditions. You have the chance to see a performer work. You also see how they deal with stress and pressure.

You may think you know the right person to cast and don’t want to audition performers. It is possible to cast successfully without auditions. If you choose this route, you might get someone who can do the job but miss out on someone exceptional.

As a festival director, I ran auditions where I saw 70 plus actors over 2 days. I was always pleasantly surprised at the breadth of talent on offer.

You may discover someone new to the scene or a side of someone that you’ve never seen. Auditioning is always worth the time. You can always fall back on the person you’d have asked anyway if the audition doesn’t get results.

Funding a theatre production

Tickets don’t always pay for everything. Staging a show costs money, and you can’t always charge your audience the total cost of the production. To bridge the gap, you need funding.

As a producer, this is a big part of your job, finding that cash.

People will give you money for three reasons:

- They want your network to get them more publicity

- They want you to succeed because its good for a community

- Out of the goodness of their hearts

The last isn’t usually enough, so you’ll need to spend time on the other two.

Sponsorship

These organisations or people are prepared to support you because they get something from it. It is usually marketing or a raise in their profile amongst their network. Sometimes the prestige of being involved with the arts helps them attract customers.

Whatever the case, they want something in return for their dollar. To get this kind of money, you need to show the sponsor:

- What they stand to gain in terms of eyeballs and profile

- Other ways they might stand to gain

- The quality of the product they’re associated

- any other things you can give them that they can use

You need to make a case that tells them they’ll benefit by helping you. A hardware store might not be interested in the prestige of the arts, but they may give you paint for free if you use their name and logo.

These arrangements are more often made as part of a discussion. A formal proposal may help for larger requests but writing a three-page letter to the hardware store won’t help much.

Always understand who you are asking and what they will value.

Grants

Many organisations want to develop a community or culture in general. They offer grants to organisations that can show them they can achieve this. They’ll want to know:

- How you plan to do it

- That you have the right skills

- That you’ll use the money carefully

Any funding proposal needs to address these things clearly and economically. Take care to use the format requested by the potential funder and provide all the requested information.

A good proposal should lay out your primary goals, what the project is and why you need support on one page. You should then provide more detailed information to show how you will achieve your goals in additional material or appendices.

Always consider any money given to you as if the funder is investing it. What is the payoff the funder wants from the investment? Unlike a sponsor who seeks a personal benefit, a funder is looking for the community benefit. Either way, it is still money given to get a result. Tailor any proposal to highlight how it helps them achieve their goals.

Ticketing a show

No matter the show you intend to present, you’ll likely have to deal with ticketing. Even free shows will have to consider it in some way. The reason is that attendance is a crucial measure of success for any performing arts project.

Suppose you are funded to deliver a free community show in a park. In that case, your ticketing may be as simple as making sure someone counts your audience. If you are inside a venue, you’ll have to control your crowd size for the sake of fire safety and evacuation. And if you want to make money, you’ll need to sell tickets.

How you manage your ticketing depends on the nature of your production, venue and goals.

The main ways to manage your ticketing are as follows:

- A specialist ticketing provider (the experts)

- An online ticketing service (modern hybrid solutions)

- Manual ticketing (doing it all yourself)

- Donation-based ticketing (passing round the hat)

Each of these has strengths and weaknesses depending on your project. For example, the specialist ticketing provider will be beneficial if you happen to have different tiers of seating (A, B reserve etc.) to manage. Yet, they will be too costly and inflexible if you are running a lo-fi show in a cafe.

Choosing the correct ticketing solution

Choosing the proper ticketing solution for your show involves considering how you plan to seat your audience, what your safety requirements are and how you’d like them to pay.

When working in a traditional performance venue and generating income through ticket sales, you are best off with a specialist ticketing provider or modern digital service.

These approaches offer advance bookings, ease of payment and do most of the work for you. You will pay fees against this income, but they are usually worth it.

If your show is in a non-traditional venue, manual door sales or online solutions offer more flexibility. You can suit your sales to the venue and the style of performance.

If you are working with a show that doesn’t rely on ticket income or uses a busker’s hat approach, you’ll need to avoid the formal providers. Just make sure you account for any safety limits or audience counting that you need to happen.

Promoting your theatre production

The goal of your promotional activities is a simple one:

- To make your audience aware of your show and get them to come along.

Choosing the best way to get this message out there is a vast and complex topic. You can use many avenues to promote a show, and these continue to grow as social and digital media mature.

The good news is that the internet has made access to promotional tools more accessible than ever. The bad news is that more people are competing for your audience’s attention than ever before.

Your promotion efforts can be separated into two main categories:

- Marketing – paid for promotional tools (e.g. posters and flyers)

- Publicity – earned promotion (e.g. Newspaper stories)

Each of these requires a different approach.

Marketing

Marketing is accessible if you have the cash to pay for it. The avenues range from the traditional, like flyers and posters, to the modern, like Facebook advertising.

No matter what delivery method you choose for your marketing, you’ll still need to craft the message. That message typically consists of two things:

- Copy – words that sell your presentation

- Visual – the accompanying images that sell your show

These are mixed to convey the correct information as effectively as possible for the delivery method. An audience has more time with a flyer than a poster, so the brochure uses more text, and the poster relies on the image.

The process of mixing these most effectively is the design. It helps to have someone who has skills in the field. Don’t let your artistic side take over. You want your marketing to communicate, not just look beautiful. There is no use in a beautiful, clever advert if you can’t work out what it’s trying to sell.

For more see our road map article, Marketing Theatre: A beginners Guide.

Publicity

Where you can pay for marketing, you need to earn publicity. Publicity can be more effective, but it is harder to get. You’ll have to get past gatekeepers, contact media outlets and convince them that your story will help them grow their audience.

To do this effectively, you need to develop relationships with the people you want to publicise. This takes time and effort, which is why many shows will use an experienced publicist. You pay for this service, but a good publicist can get your message indoors. Other people may not.

Once your publicist gets you an opportunity, you’ll want to maximise it. As many publicity opportunities involve interviews (live or otherwise), you’ll need to be ready to talk about your show.

Doing this effectively relies on you knowing what to say, so it pays to develop a set of talking points. There are two types of information in the talking points:

- Factual information (where is the theatre, what times is the show etc.)

- Selling points (why an audience member would want to come)

If you miss out on either of these, your message will fall short.

Designing a theatre production

Anything on the stage that isn’t a performer is subject to a design of some sort.

There are many sub-disciplines of show design. Each typically aligns with an area of technical expertise. The design lays out how each element helps create the overall show the director/choreographer/producer asks for.

While many specialisations of design exist (e.g. acrobatic designer), most emerging producers will deal with a small handful. Lighting, sound, set, and costume are the most common. You’ll need to plan how you intend to approach each of these (or any other elements that fit your show).

The design

The key to a good design is to work out what you need to achieve your goals. A good designer can help you identify how to do that. If you hire a designer for every task, your wage bill will quickly outgrow your budget.

Thankfully hiring an experienced designer can save you money in materials and labour. Modern art has many different aesthetics, and a professional designer will know which can work within your budget.

There are straightforward, simple tactics you can employ to achieve a suitable design at an affordable price.

Getting technical

For each of the main areas of design, you’ll need someone who knows how to make things work. A good technician is worth every cent they charge.

There are some key considerations when assembling your technical team.

- You need to cover all the essential skills

- You need to cover install AND operation

- Many technicians are capable designers (and vice versa)

- A complex production may need some to coordinate all the moving parts.

In most shows, you’ll want someone who can operate lighting and sound at the very least.

Rehearsing the show

Rehearsals are where you build your show. You’ll take all the pieces, assemble them and practice until everything works smoothly. A producer’s roles are primarily to make sure there is enough time and resources.

Time

There are many different patterns for rehearsals, but there are three main areas you’ll need to think about.

- Devising – creating the show itself

- Rehearsing – practising & polishing the performance

- Technical – integrating the technical elements into the performance

Different productions will allocate different amounts of time to each of these. For example, if you work with a published script, there will be no devising phase.

You need to ensure that you allocate enough time to achieve each phase. Your director and/or dramaturg can guide you on the first two. Your designers and technical team can help you with the third.

Where to rehearse?

The other thing to worry about is a space to rehearse. Devising and rehearsing usually happen away from the theatre. Your technical rehearsal typically occurs in the venue, so make sure there is enough time there.

You’ll need a comfortable room that is the same size or bigger than your stage in an ideal world. Aside from that, your director or dramaturg may have some special requests.

Don’t forget that people have needs. You’ll want an easily accessible bathroom, and a kitchen can also be beneficial.

Performance

Finally, it’s time for the performances—the most exciting time of any production.

Venue

Finding the performance venue that suits you is crucial. There are many considerations to choosing a suitable space. Size and number of seats are the more obvious considerations. Yet, less obvious things, like the venue’s culture or its built-in audience, can have much more effect.

Running the show

For any show, there are some key elements you’ll need to plan for.

- Making sure the performers and crew can do their jobs

- Making it easy for the audience to get to their seat

- Keeping everyone safe if something happens

- Coordinating front and back of house

In a traditional theatre, this stuff is usually already arranged. You’ll have ushers and a ticketing team. They will communicate with the stage manager, who looks after the cast and crew.

If you work in a space that isn’t designed for shows, you may have to put all of this in place for yourself.

Conclusion

The aim of this article was to introduce you to theatre production and give you a road map that can guide you.

We’ve covered a lot of ground at the top level so if you want to go deeper on any topic click through to linked articles and keep up with our new content.

We also recommend you check out our other road map content: