Budget 201: Making a more accurate theatre budget

Beyond the basics: Making your theatre budget more accurate.

Introduction

In Budget 101, you made an initial budget, and as you started to build an outline, you may have found yourself with questions. There may have been things that seemed just a little too simplified. If you did, you’re right. But at least now you have an idea of what else you need to know.

This article will look into more detailed approaches to dealing with ticketing costs. We’ll also look at making better estimates for your expected audience size and discuss what that does to things like ticketing costs.

Different Types of Costs

Let’s start by taking a closer look at costs. We know that costs or expenditure is what we spend to make the show happen. Yet you can break costs down into types based on how you need to treat them in your budget.

To build a show budget, we’ll look at two main types, fixed and variable.

Fixed Costs

A fixed cost does not change with the size of the audience.

For example, if you buy timber to build your set, the cost will be the same no matter how many people sit in the audience. This cost only changes if you change the set design.

Most costs you deal with will be fixed. They shouldn’t change unless you change the plan.

Variable Costs

A variable cost does change depending on the number of tickets you sell.

Imagine you’ve decided to hire an usher to help seat your guests. Your theatre seats 100 people and has rules that an usher can only manage up to 50 guests. If you sell more than 50 tickets to that performance, you’ll need to hire another usher, which means your wage cost doubles.

The most common example of variable costs you’ll deal with is the service cost of selling tickets. A ticket vendor may charge you a fee per ticket to sell tickets for your show on your behalf. That means, for each ticket sold, ticketing costs will increase.

Is it the same for Income?

Yes. Like costs, income can be divided into variable and fixed income.

Again, fixed income does not depend on ticket sales.

Typically, your fixed incomes come from funding, sponsorship or donations. Funding or sponsorship rarely vary depending on how many tickets you sell.

Selling tickets is the most obvious example of variable income. The more tickets you sell, the more money comes in. But, of course, this extends to anything that changes with the audience, like program or snack sales.

Dealing with Theatre Budget Variability

So with variable costs and income, how do you manage a budget that can change?

It would help to know what happens in certain situations. In Budget 301, we’ll talk about budget sensitivity and how to account for these changes by building different scenarios into your budget.

But for now, we’ll focus on linking those costs and incomes to audience numbers so that they change simultaneously.

Going back to basics from Budget 101, we know that calculating your audience based on an estimate of 30% is ok. If we have a five performance season in a 100 seat theatre, it looks like this:

- 5 shows x 100 seats = 500 tickets available

- 30% of those tickets sold = 150 tickets sold.

- 150 tickets sold at $20 ticket price = $3000 income from ticket sales

It is no surprise that if that percentage changes up or down, the ticket sales will follow.

To make sure you don’t have to do this calculation every time the number of tickets sold changes, you can use a formula in a spreadsheet. Stay with me here, it’s easy maths, but if you aren’t cool with spreadsheets, it might require some focus.

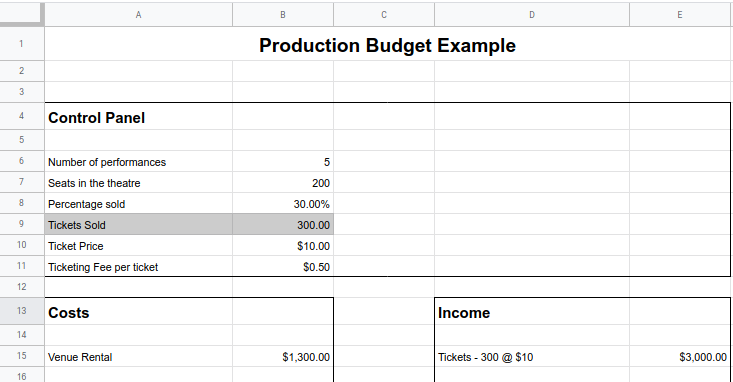

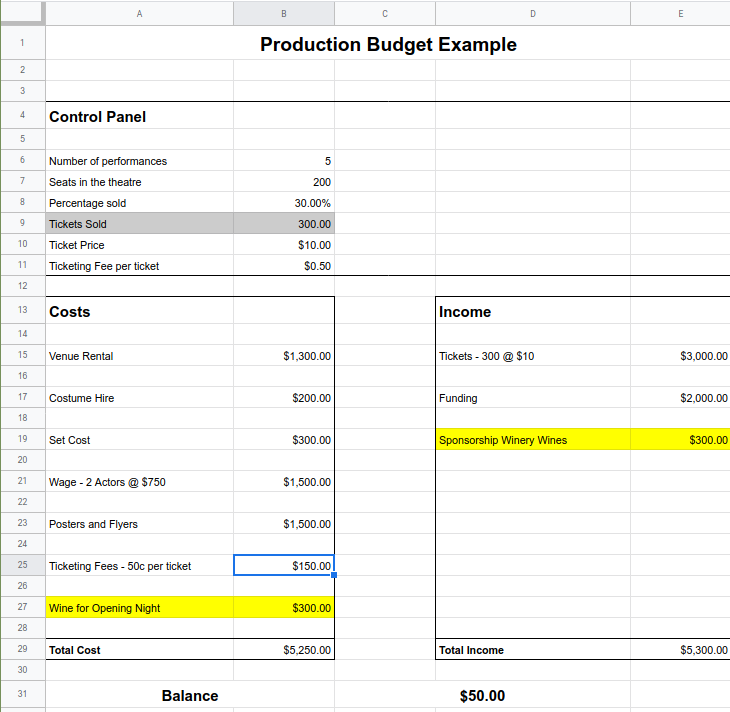

As you can see in the image, we’ve moved the things we may want to change to the top. So, for example, you can input new figures for tickets sold or even the ticket price.

Then in the cell where we listed the income from tickets sold, we now put a formula. This is a fancy way of saying we tell Sheets to multiply the number of tickets sold (in cell B9) by the ticket price (in Cell B10) and put the answer in the ticket income cell (cell E15).

The formula looks like this: =B9*B10

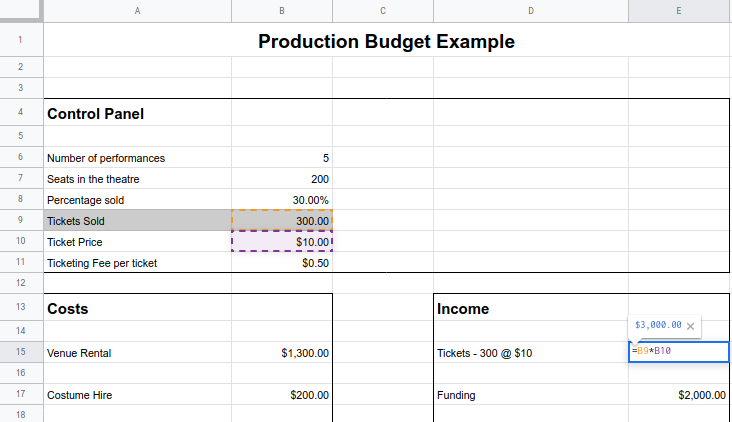

You can extend this idea to other things that depend on ticket sales. For example, the following photo shows the same process for ticketing fees.

You can create a section at the top to use as a Control Panel to allow you to make quick changes. You may wish to break tickets sold down into a calculation too, where you can change the number of shows, seats and percentage sold.

This approach serves to make your life much easier. You don’t have to get your calculator out when something changes because the spreadsheet updates itself when you change the correct cell.

How many Tickets?

So when you look at variable costs and incomes, it is clear that the number of tickets sold is significant. So if you sell less than predicted, you will not have as much money and vice versa.

So you will want to make sure you have a reasonable estimate for ticket sales when you begin to plan. In our theatre budget 101, we said the range should be between 25-40%, and while those numbers help, there are other ways to estimate this.

Try this exercise.

Sit down and make two lists.

- Will come – guaranteed! (eg. Mum and Dad)

- Might come – if I ask (e.g. My high school friends)

Then write down everyone you know who fits on each list.

- Add up the numbers on each and keep your two totals.

Now total up how many people are in the cast and crew.

- Only include people who have a significant connection.

- Don’t include anyone only there for a paycheck

Now take the number of people and multiply it by the total on each list.

- 14 – Will come

- 25 – if you add Might come to Will come

- 10 – cast and crew

- So your two numbers are 140 & 250

You now have an Estimated Range

So a reasonable guess is that you can count on somewhere between 140 – 250 people to attend the show.

Now marketing might improve these numbers, but this should give you a range for the worst-case scenario.

It also helps to compare it with percentages. For a five-show season in a 100 seat theatre, 25% is 125, which is in line with the bottom figure. At 40% it is 200 which is inside the top figure.

If you are very social and well-liked, your list may be longer than a more introverted person. So it can help you even more if you can get others to do the exercise. If you have three sets of numbers from three different people, your estimate will be better. With the Will come numbers from three folks being 14, 10 & 15 you’ll be able to average that to 13 x 10 = 130 people.

Other Avenues of Research

If you’d like to refine your estimate, even more, you could try one of the following things:

- Ask friends who’ve produced what their final average was

- Ask experienced producers what percentage estimate they use

- Attend other shows that have similar audiences to yours

- Run an online survey about who might attend and at what price

- Look at the attendance of other shows via a funder or venue partner

- Enquire with your ticketing provider about their experience

Money isn’t everything.

It’s true to say that there are things you’ll get for nothing and things you’ll have to give away for nothing. But it is vital to make sure you remember they still have value. So dealing with this is another essential part of theatre budgeting.

Imagine a business giving you 20 bottles of wine for free (which you can use to support your show). In return, they ask that you put their logo on your posters and thank them in the program. No money changes hands, right?

Physically, no, but there is an exchange in value. The winery paid you 20 bottles of wine to advertise to your audience. So the question is, how would that fit in a theatre budget if no cash was involved? Does it even need to go in?

The answer to the second question is a definite yes, for reasons we’ll explain later on. The question of how to get it into a budget is what we’ll focus on now.

An example

You walk through the supermarket one lunchtime, and you find the very same bottle of wine on the shelf for a retail price of $15.

So if you’d paid for the wine you were given, you’d have spent 20 x $15 = $300. So those bottles of wine are almost the same as being gifted $300 (especially if you’d have bought them anyway). So the winery paid $300 for that advertising.

Later, when you are getting your posters made, you ask the designer to add the winery logo, and they do so at no additional cost. The advertising cost you nothing.

But if you think about how many people will see the poster and flyers, 300 dollars is a pretty good deal.

As an aside, the winery only paid the wine’s cost price, which makes the deal even better. Mentioning this is only relevant to theatre budgets in that you should always understand the value of what YOU have to offer. Maybe you could have gotten 30 bottles?

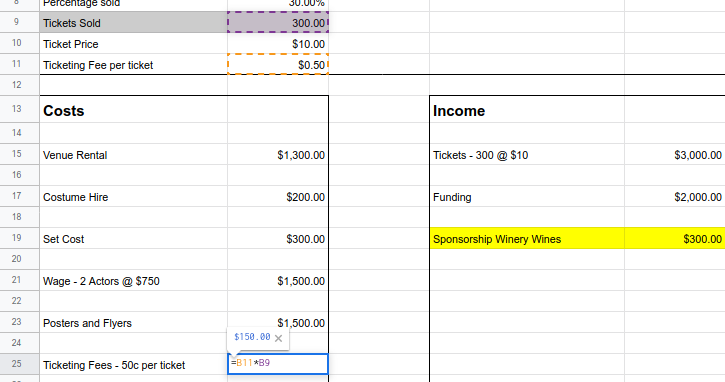

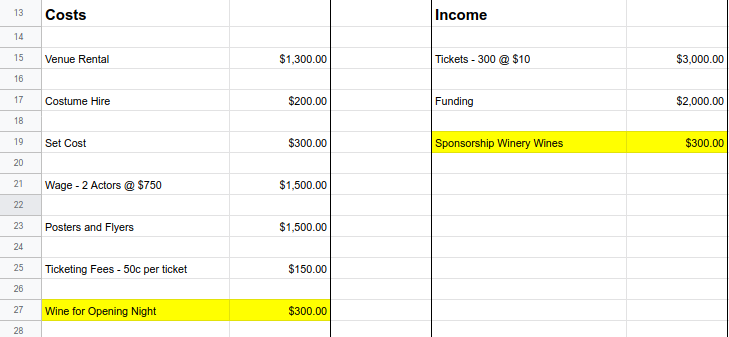

We need to reflect that we’ve been given $300 worth of product in the budget. So it’s best imagined like this: The winery gave us $300 cash, and we bought $300 of wine with it.

In the theatre budget, we add $300 of sponsorship in the income column, reflecting the value of the wine. Then we record the purchase of 20 bottles of wine at $15 on the costs column to balance it out. See this in action below.

Free stuff in a theatre budget? Why?

Fair question. After all, it seems a bit strange to put an item in twice when you paid nothing for it at all. Wouldn’t it be easier to leave it out?

Yes, it would be more straightforward. That is until you apply for funding.

One of the things funders look at when deciding if they will support you is how much support you have already collected. This is because a well-supported project is more likely to succeed, making you a better use of their money.

So it is important to show every bit of support you are getting. You may be leaving a lot out if you overlook the free stuff.

If a student radio station plays ads for free (or even a discount), you can record that as support because otherwise, you’d have spent that money. Likewise, if a company donates the materials for your set, that is the same as a funder paying for it.

So if you don’t include it in your budget, they won’t see it. Listing the value of free items, goods in trade, or even discounts supporting your project allows you to show a true and accurate picture of your financials.

Also, the fact you’ve thought to add these items to your theatre budget show’s your attention to detail and makes you look like a pro.

What about things I give away?

Alongside dealing with free stuff you’ve been given, you’ll also have to account for the free stuff you give out.

What am I giving out for free? Again like the support, there is no physical exchange of cash, but there is an exchange of value.

Mainly, you’ll be dealing with complimentary tickets. You may exchange them for publicity reasons or as part of a larger arrangement. You might even be able to trade them for goods.

The most straightforward example is a reviewer’s ticket. They come to the show for free, but they write a review that may help you sell tickets. Perhaps you have a friend who has social influence or will talk about your show a lot. If you give them a free ticket, you’re paying for publicity.

There are two ways of looking at this in your budget. First, you can treat comps as a standard cost of doing business and account for them as ticket sales of $0. Or you can add them to both sides of the budget as you did with the sponsorship.

Most comps will have some publicity effect, but it is hard to give them a value. This applies to comps you offer cast and crew. Typically, the best approach is to treat them like a simple cost.

Yet, if you give comps to a media organisation for their use, these are effectively a cash substitute. You gave the organisation tickets in exchange for a service where you would have given cash. In this case, you should reflect the value of these tickets somewhere in the budget.

For example, Radio Friendly gave you advertising worth $200 in exchange for 20 ten dollar tickets. Therefore, the advertising cost is $200, and the cash value of the tickets can be listed under income as a donation. A comp ticket given away costs you the possibility of selling it. That isn’t an actual cost (aside from the ticketing fee), but it is an opportunity cost (which takes a lot more effort to list in a theatre budget).

Conclusion

This article extended Budget 101 and added the crucial ideas of variable costs and incomes. It is also linked to their reliance on ticket sales and how to keep track of them when numbers change.

In doing this, we brushed very lightly on the idea of using formulas in a spreadsheet. For more on spreadsheets, you should look at the Google Sheets documentation.

This quickly led to needing better audience estimation systems. Working out how many people will come is probably the most important thing to prepare your budget. We’ll address how you can make this even more helpful in Budget 301.

It also approached dealing with donated goods and services and why to include them in a theatre budget. As funding is often crucial to success, it is vital to create the best possible budget picture to support applications.

Budget 301 will extend into the ideas of theatre budget sensitivity, add more complex approaches to the control panel and offer some suggestions about valuable layouts.

If you are looking for more information on producing in general check out Theatre Production 101.